Ecological connectivity is key to the life cycle of the species that inhabit the Mesoamerican Reef

Fish known as blue chromis swimming in the coral reefs of the Punta de Manabique Wildlife Refuge in Guatemala. Photo: Sergio Hernández/CONAP

By Lucy Calderón

Allured by the beauty of the sea and attempting to understand its power, Eloy Sosa-Cordero pursued an undergraduate degree in Oceanology at the Autonomous University of Baja California and a master’s degree in Marine Ecology at the Ensenada Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education (CICESE, in Spanish), located in Baja California. He gradually geared his interest and field of action towards fisheries because, as he explained, there is so much to learn from these topics.

“First, I was interested in how the laying of small eggs produce fingerlings and larvae, which later become fish of commercial interest for human consumption. Then, I carried out fish monitoring, and now, I am conducting a survey with fishers to know about their health and financial situation, and their basic needs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. After 30 years in the fisheries sector, this is the first time I am conducting this type of survey. The results will be included in the first report on the current conditions of fishers in the Mexican Caribbean. The report will be published by El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), of which I coordinate the Chetumal Unit,” Eloy said.

Eloy said that in 2004 he worked with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a scientific agency of the U. S. Department of Commerce. Back then, a group of Florida researchers who were studying the recruitment of Bluefin tuna also became interested in determining if there were spawning areas of this species in the Mesoamerican Reef System (MAR).

Another reason that drove them to obtain this type of information is that, with climate change, species might vary their spawning areas, therefore researchers began to study fish larvae and juveniles. Eloy’s wife, Lourdes Vásquez-Yeomans, a Science teacher and researcher, is an expert in fish ecology and their early stages. She worked along with NOAA in joint projects, and coastal and open sea monitoring using cruise ships, “a fine combination, but quite costly,” Eloy explained.

As a result from that participation with NOAA, the issue of ecological connectivity arose: the importance of knowing the connection that might exist between areas and marine species in the MAR. Then, ECOSUR – together with the Mesoamerican Reef Fund (MAR Fund)-, organized workshops on this topic.

Eloy commented that a good collaborative spirit was consolidated from these workshops and with MAR Fund’s support. The joint implementation of the Mesoamerican Connectivity Exercises (Ejercicios de Conectividad en el Sistema Arrecifal Mesoamericano [ECOME], from Spanish) was led by ECOSUR.

The first meeting of the ECOME Network that was formed in 2010. Photo:MAR Fund

What is an ECOME?

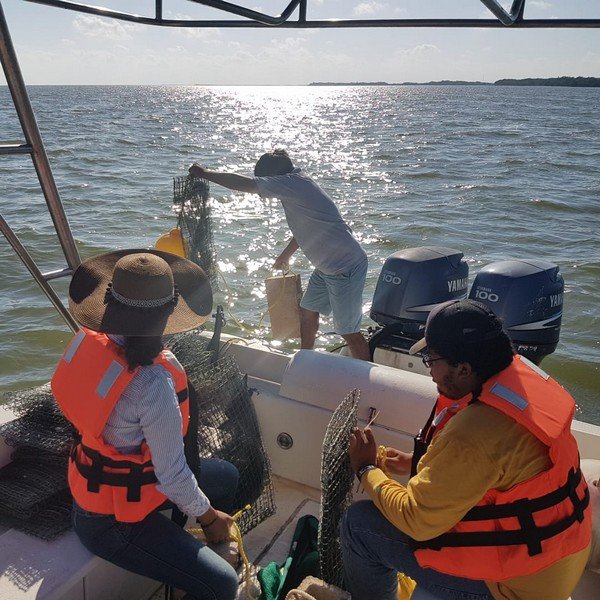

People taking part in an ECOME in the Yum Balam Flora and Fauna Protection Area, Mexico, preparing collectors to harvest postlarvae. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

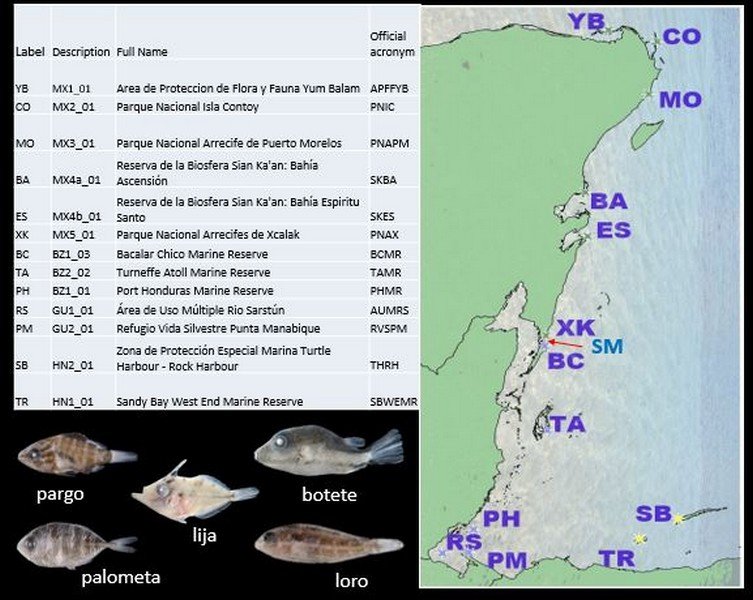

An ECOME is a monitoring exercise carried out simultaneously in the region by the local staff of each marine protected area in the four countries that make up the MAR (Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and Honduras).

The objective is to place the collectors (similar to cylindrical bags) in places where fish postlarvae might be found, and harvest some of them to learn about the abundance (or quantity) and richness (or diversity) of species –of commercial or ecological interest– found in selected areas.

Although with many financial and staff limitations, the ECOME are conducted every year in the MAR since 2013, in at least two marine protected areas per country, Eloy explained. So far, nine ECOME have been conducted.

In 2018, through MAR Fund’s Small Grants Program, ECOSUR was awarded funds to implement the project Participatory Monitoring of Reef Fish Recruitment: Connectivity indicator in the Mesoamerican Reef . Thanks to the financial support, two ECOME were conducted simultaneously in two areas per participating country, one in October 2018 and the other in March 2019, which was a great achievement, Eloy added.

Three workshops were also carried out: two with Mexican fishers and one in Belize, with the staff of protected areas of the four countries. “We explain to the fishers the life cycle of fish, how eggs produce larvae, and how these travel through the ocean and then return as postlarvae to the coast for growth. We also explain to them what an ECOME is and invite them to participate with us in future studies of this type. Something that gave us great pleasure was that, in addition to people linked to community groups, the fishers’ wives also attended. They are less shy and ask again and again until they have a full grasp of the subject,” Eloy said.

The workshop aimed at protected areas staff focused on training them on the use of oceanographic devices, particularly learning how to use the sensors that measure water temperature, which were acquired for the project and delivered to representatives of each participating area.

Workshop with fishermen of the Yum Balam Flora and Fauna Protection Area, Mexico. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

During the workshop held in Xcalak, representatives of natural protected areas learned to recognize fish species in postlarval stage. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

When to conduct an ECOME?

Participants of an ECOME conducted in Bacalar Chico, Belize, inspect the collectors. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

It has been reported that during the new moon season, when it is dark, the small larvae that hatched from the eggs laid by their parents on the full moon, return to the coast after the currents have carried them away, Eloy indicated.

“But nature is very wise,” Eloy adds. In the darkness, the larvae that have managed to survive hunger or their predators return as postlarvae to their breeding grounds, among mangroves and seagrass, until they reach the right size to reproduce again. And this cycle is repeated every year. Then, collectors are placed on the selected sites three or five days before the new moon, and they are inspected daily up to four or five days after the mentioned moon phase.”

In this project, funded by MAR Fund, all participants per country checked the collectors in the morning, between 6:30 and 9:30. And they would share how they did and send pictures of the collected larvae through their WhatsApp chat group. “Creating this support network –very encouraging– was also one of the project’s objectives,” Eloy said excitedly.

Participants in the workshop held in Punta Gorda, Belize. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

What is so special about a regional and participatory ECOME?

Collectors are brought to the surface in a bag that facilitates their transportation. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR. Location: Roatán, Honduras

All participants use the same collection equipment and follow the same methodology to collect the samples. They conduct the exercise on the same dates, times, and, if possible, at the same depths for effective comparisons. Work protocols prepared by the staff of ECOSUR and NOAA were shared. Sergio Hernández, an aquaculture specialist of the National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP, in Spanish) in Guatemala, who participated in the project, said that thanks to the information obtained from the ECOME, they are able to determine –for example– the number of specimens captured from one postlarval species; if there are more commercial or herbivore species; the diversity of species collected. They are also able to learn about the events or processes that might be affecting their presence in the selected areas, among other aspects.

What happens after collecting the postlarvae?

There is a protocol to conduct the ECOME. When an unknown species is collected, it is preserved in alcohol and then sent to ECOSUR, where the researcher and expert Lourdes Vásquez-Yeomans can conduct genetic studies that will allow identifying those species visually hard to recognize, Hernández explained.

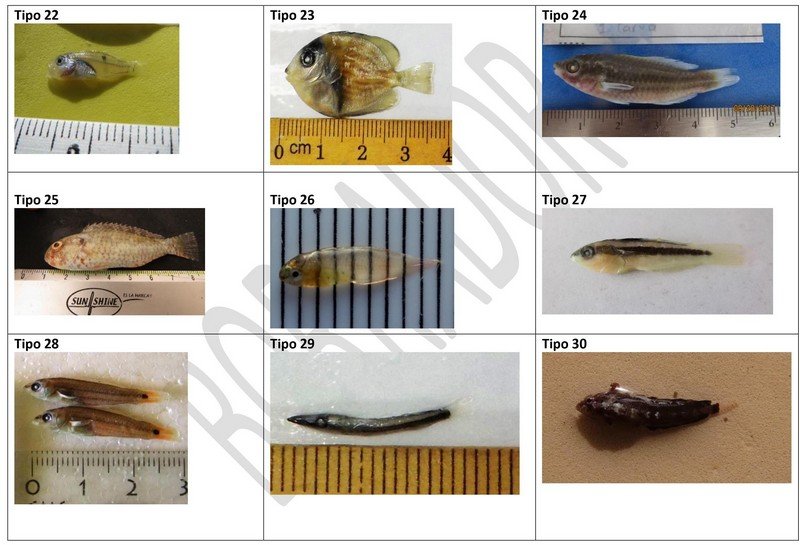

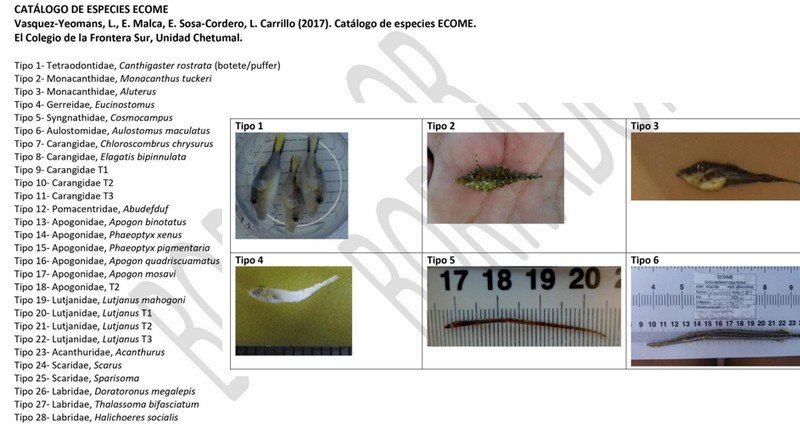

On the other hand, when a known species is captured, a ruler is placed beside it to measure its size and a photograph is taken, it is identified, and then released back to the sea. A catalog is available to identify the larvae, which is a technical resource for the identification of different fish species.

Species included in the ECOME species catalog, prepared by Lourdes Vásquez-Yeomans, Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

What are the results of this regional ECOME?

This studies have been conducted at least once a year in the MAR since 2013, although with some variations based on the possibilities of each area. Historical records are now available for many of the areas that participated in this project funded by MAR Fund.

The collectors we use are selective, affordable, and simple, so they only catch some of the fish species. The species that we usually find and found this time included snappers, grunts, and mojarras. Sport fishing species included jacks and permits. And those with ecologic importance included parrotfish, tangs, and pufferfish, Eloy described.

In the case of Mexico and Honduras, we noticed that the abundance of parrotfish has increased, which is a good sign because they play an important role in reefs. They feed on algae and prevent them from covering the corals that die from lack of light and nutrients, Eloy explained.

We also identified some coincidences. For example, the number of postlarvae and small juveniles that come into the collectors decrease when there is a large amount of Sargassum. We don’t really know why, but we find it interesting that it happens with the occurrence of Sargassum, the professional indicated.

Sargassum in Bacalar Chico, Belize. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

In Guatemala, Sergio commented that the Sarstun and Punta de Manabique sites are very different from the rest of the marine protected areas participating in the regional ECOME. Reefs are deeper and diving gear is required to go down to place the collectors and then remove them. “The tasks in these two areas are very demanding, even to arrive to the selected sites for collection,” Eloy explained. He also added that “the richness of species in Guatemala is significant because it contributes with information on some species that have only been recorded in that country during the ECOME, among them, the labrid fish Halichoeres socialis.”

A barracuda in the Punta de Manabique Wildlife Refuge, Guatemala. Photo: Sergio Hernández/CONAP

Blue chromis fish swimming in the Punta de Manabique Wildlife Refuge. Photo:Sergio Hernández/ CONAP

How important is an ECOME, and what are its results for?

Example of a map of marine protected areas participating in the ECOME and a sample of the fish found. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

Eloy said that, while simultaneously monitoring several areas, it is possible to learn how similar the processes are occurring in each area.

Sergio explained that the obtained results allow adopting measures to regulate fisheries, avoid overfishing and contamination of seas and oceans, teach fishers to avoid catching fish during their reproductive stage, and encourage them to conserve mangrove and seagrass areas which are essential for the breeding and growth of commercial fish species.

“Most importantly, by highlighting the sites with higher diversity of species, it promotes further research in these areas and their conservation. Collected data can also be shared with other institutions working on the protection of marine areas and fisheries resources. There can be better planning of actions to improving no-fishing zones near coral reefs in order to keep encouraging marine conservation,” Sergio added.

Where to find the results from each ECOME carried out so far?

Catalog compiled by Lourdes Vásquez-Yeomans of ECOSUR. Photo courtesy of ECOSUR

Eloy said that the representatives of each protected area participating in an ECOME enter the obtained results from the exercise in their own database. There is also a data repository in ECOSUR, continuously updated by M.S. Vásquez-Yeomans. She prepared a catalog including the species found in the marine protected areas of the MAR that have participated in the exercise.

For more information, please write to Eloy at esosa@ecosur.mx

Tags: Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), COVID-19, ECOME, Exercises in the Mesoamerican Reef System, Mesoamerican Reef Fund (MAR Fund), Mesoamerican Reef System (MAR), National Council of Protected Areas (CONAP), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), postlarvae, Punta de Manabique Wildlife Refuge, Yum Balam Flora and Fauna Protection Area